- British businesses have suffered declines in EU trade.

- Billions-worth of investment assets have left the UK, opting for EU states.

- Bucking the trend, fine wine prices soared to heights of 43%.

By the end of 2019, 70% of Brits were already nauseous of the word ‘Brexit’. But behind the fatigue, there was real fear in the air too. As the customs rules came into effect in 2021, gridlocked lorries clogged the roads to Dover, paperwork mounted, and supermarkets shelves began to look increasingly bare. The end of the single market had begun. The past years have been sobering time. According to the latest poll in January 2024, 61% of Brits would vote to rejoin the EU, up from 55% in summer 2023.

But what about the investment markets, and the performance of fine wine? In this article, we are diving into some of the main impacts of Brexit so far.

Added complexity dampened profitability

81% of UK businesses are still struggling with Brexit admin. For wine traders, the paperwork for a single bottle can stretch to over 90 pages, adding significant workloads. UK manufacturers are particularly suffering, with 96% reporting that the new rules have ‘badly disrupted trade with the EU’.

More compliance means more costs. It is estimated that businesses have spent an average of £100,000 each just trying to export goods over the border in the past years.

The complications have also led to once-loyal European customers jumping ship, with the average enterprise missing out on £96,281 since 2020. Two in five UK manufacturers have experienced declines in export volumes.

‘Brexodus’ carried talent (and investment) out of the UK

It is little surprise therefore that busloads of businesses, staff and operations decided to relocate. Welsh wine exporter Daniel Lambert, for example, moved his company to France in 2022. Lambert supplies some of the biggest British supermarkets, including Waitrose and Marks & Spencer.

Dublin has been one of the major hotspots for financial services, snatching-up the UK’s crown as the English-speaking bridge to the EU. This ‘Brexodus’ as it came to be known was great news for European cities. Germany, for example, enjoyed a 21% increase in direct foreign investment in May 2023.

However, it did not bode well for the UK. By March 2022, 7,000 jobs within financial services moved to the EU. Investment funds left too, with 24 firms planning to transfer £1.3 trillion of assets. Funding for British markets faltered.

As a biproduct of Brexit, the supply of skilled EU workers dwindled too. Today, recruiting European talent is 44% more difficult for UK companies. December 2023 saw the launch of even stricter measures designed to curb the flow of foreigners, although it also introduced higher minimum wages for skilled workers.

Slow growth turns off investors

Brexit was accompanied by the Covid-19 pandemic, political instability, and war overseas. While it is difficult to untangle the impact of Brexit, the UK has been notably slow to recover compared to peers. The Eurozone, for example, has grown at more than double the UK pace.

Increasingly, data suggests Brexit threw a wet towel on the UK’s growth prospects. As Jonathan Portes, Professor of Economics and Public Policy at King’s College London, highlights, ‘both aggregate data and survey evidence strongly suggest that Brexit is at least in part responsible for the particularly poor performance since 2016, with investment perhaps 10% lower than it would otherwise have been’.

2024 analysis by the National Institute of Economic and Social Research corroborates, stating, ‘UK real GDP is some 2-3 per cent lower due to Brexit’. Each household is now £850 worse-off following Brexit, rising to £2,300 by 2035.

The retail wine market has suffered but not fine wine

Since Brexit, supermarket wine has had an estimated price increase of £3.50 per bottle. Perhaps in response, the government recently announced measures to ‘cut red tape’. The definition of wine will change to allow for wine mixing, lower alcohol volumes, and even pint-sized measurements.

The prices of fine wine went up too. Investment grade bottles, such as those traded on WineCap, performed exceptionally well during the turbulent Brexit periods. Many investors found fine wine hedged their portfolios against losses elsewhere.

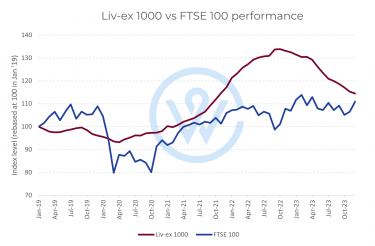

The graph below shows the performance of the broadest fine wine market measure (Liv-ex 1000) over the past five years.

In the run-up to the customs changes, fine wine prices rose during mid-2020. Over the following two years, they saw an increase of 43%. This is in stark contrast to the performance of the FTSE100.

The returns didn’t end there. Because of fine wine’s unique tax status as a ‘wasting chattel’ in the UK, nearly all bottles are exempt from costly capital gains taxes. For those earning over £50,271 a year, this means savings of up to 28%.

To invest or not to invest?

Despite taking hits from Brexit, the UK is still an investment hub. Tourists are returning to London, businesses are battling through the headwinds, and gradually it is becoming clear that there needs to be more cooperation with the EU.

Throughout this turbulent time, fine wine has reached new heights. The (potentially Brexit-induced) combination of the weak pound and high dollar opened the floodgates for foreign fine wine investments. And the UK’s thriving tech scene also created inroads for savvy digital investors to trade fine wine. Investors have made the most of these glimmering opportunities to batten-down the hatches and shield their portfolios against some of the other Brexit difficulties.

If you are looking for a smooth way to invest in fine wine, our experts at WineCap are happy to guide you through the journey. Unlike Brexit admin, we are just a call away.