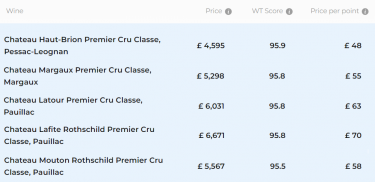

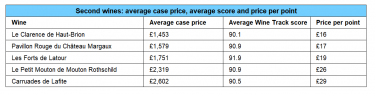

- The average First Growth case price is £5,300, while second wines come in at £1,941.

- Le Clarence de Haut-Brion is the most affordable second wine.

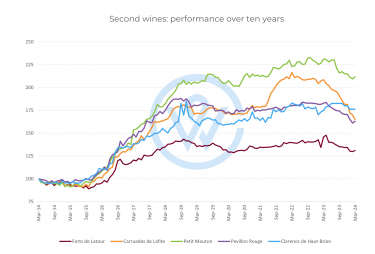

- Le Petit Mouton has been the best performer over the last decade.

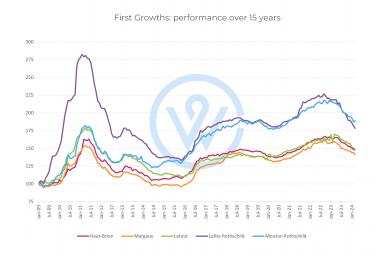

Following our article last week examining the performance and value of the Bordeaux First Growths, we now turn to an important but often overlooked category within Bordeaux wines: second wines. These wines offer investors a compelling balance between brand prestige and affordability, making them increasingly relevant in today’s fine wine market.

This analysis explores what second wines are, how they compare to their Grand Vins, how they are priced, and why their long-term performance makes them attractive within a wine investment portfolio.

What are second wines?

Most leading Bordeaux châteaux – particularly those classified under the 1855 Classification – produce more than one wine per vintage. Alongside the Grand Vin, many estates bottle a second wine (sometimes referred to as a “2nd wine” or “wine or second label”), and a handful may even produce third or fourth wines depending on vineyard size and stylistic goals.

Second wines generally come from:

-

younger vines, which may not yet deliver the depth required for the Grand Vin

-

vineyard parcels that do not fully meet Grand Vin quality in a given year

-

fruit that is stylistically better suited to an earlier-drinking profile

Despite this, second wines often receive the same technical treatment – from vineyard work to vinification – as the flagship label. They may use fruit from the same renowned terroirs, the same cellars, and benefit from the expertise of the same winemaking team.

For investors, this means second wines offer brand access at a significantly lower price, while still carrying the hallmarks of top Bordeaux estates.

Second wines: Pricing and Value Dynamics

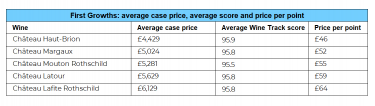

Price Comparison: First Growths vs. Second Wines

The average First Growth case price sits around £5,300, reflecting their iconic status within Bordeaux’s hierarchy. In contrast, the average price for a second wine is £1,941 – less than half the price, yet still benefiting from strong brand associations.

This pricing gap offers investors a more approachable entry point to the top tier of growth wines, particularly within Saint-Julien, Pauillac, and Pessac-Léognan, where some of the world’s most admired estates are located.

Where prices diverge

Interestingly, the price hierarchy of the Grand Vin does not always replicate itself in the second-wine market.

For example:

-

Château Latour produces one of the most expensive Grand Vins after Lafite Rothschild.

-

Yet its second wine, Les Forts de Latour, sits mid-range in pricing compared with its peers.

-

Meanwhile, Le Petit Mouton (from Mouton Rothschild) and Carruades de Lafite (from Lafite Rothschild) are priced higher, reflecting exceptionally strong brand demand.

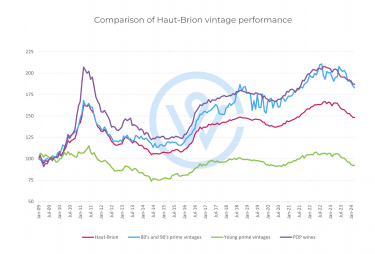

Similarly, Le Clarence de Haut-Brion – the second wine of Château Haut-Brion, one of the most historically significant estates in the 1855 classification – remains the most affordable of the second wines despite its pedigree.

This shows that market demand, not just classification, shapes pricing for second wines.

Scores and price-per-point

When examining value for money, score-based metrics offer useful perspective.

-

Le Clarence de Haut-Brion holds the lowest price-per-point (£16) among second wines, mirroring Haut-Brion’s reputation for over-delivering relative to price.

-

However, while Haut-Brion Grand Vin scores very highly on the Wine Track Index, Le Clarence’s score is comparatively lower.

This disconnect illustrates a key point: For second wines, price does not always correlate closely with critical ratings.

Instead, a different dynamic typically governs their appreciation.

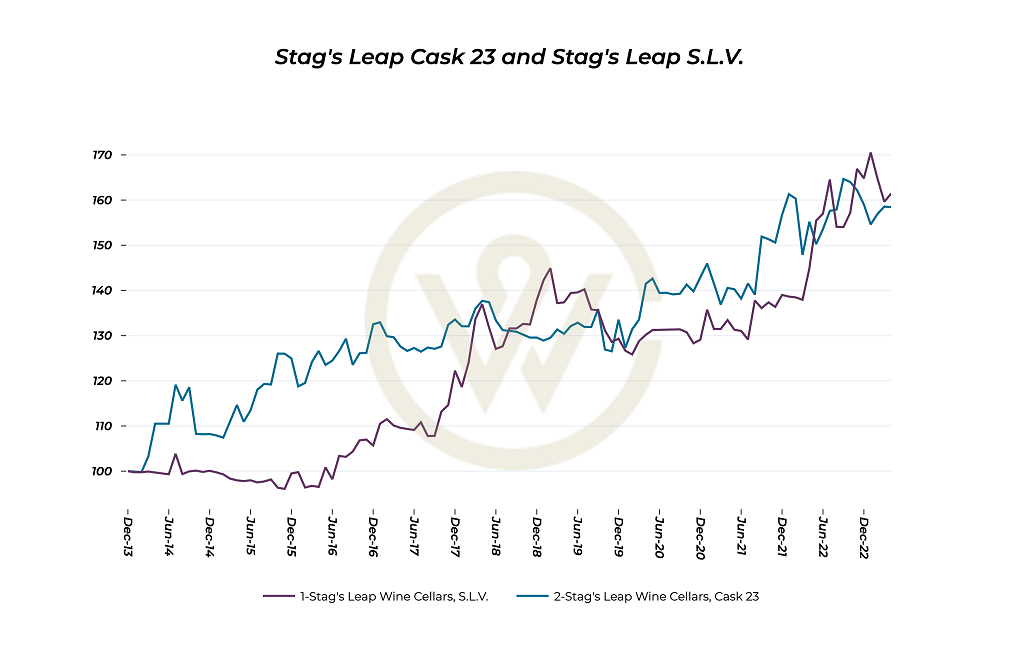

Second wines behave differently from the Grand Vin

With Grand Vins, price is strongly driven by quality, scores, and global demand.

For second wines, however, the dominant relationship is between price and age. As bottles are consumed and availability reduces, the scarcity effect naturally lifts prices.

In this way, second wines often follow the traditional wine investment ageing curve, appreciating steadily regardless of whether they score as highly as their Grand Vin counterparts.

They also present:

-

brand access for collectors who may be unwilling to open a £500+ bottle

-

earlier drinking windows, which attract both consumers and restaurants

-

strong demand on release, especially for estates like Mouton Rothschild, Haut-Brion, and Lafite Rothschild

Second wines therefore fulfil both a consumption and investment role, ultimately supporting more stable long-term price performance.

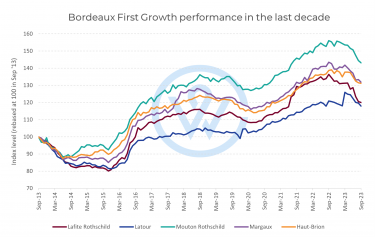

Performance of the Bordeaux second wines

Over the past decade, second wines from the top estates in Saint-Julien, Pauillac, Saint-Estèphe, and Pessac-Léognan have shown strong appreciation.

Top performers (10-year performance)

-

Le Petit Mouton (Mouton Rothschild)

+111.9% – The strongest performer, reflecting exceptional brand equity and global demand. -

Le Clarence de Haut-Brion (Château Haut-Brion)

+76.2% – Undervalued on release, this wine has delivered impressive mid-term returns. -

Carruades de Lafite (Lafite Rothschild)

+64.7% – One of the most globally recognised second wines, with strong demand across Asia. -

Pavillon Rouge du Château Margaux (Margaux)

+63.1% – A consistently sought-after second label with stable year-on-year appreciation.

These figures highlight how second wines from Bordeaux’s most prestigious châteaux can generate meaningful returns, often outperforming mid-tier Grand Vins and offering a lower-risk route into blue-chip Bordeaux.

Why Bordeaux second wines matter for investors

Second wines sit at the intersection of:

-

prestige (access to top-tier châteaux)

-

affordability (compared to Grand Vins)

-

liquidity (strong global recognition)

-

age-driven price increases (steady appreciation over time)

For investors building a Bordeaux wine portfolio, second wines provide:

-

diversification across vintages and price points

-

exposure to world-class estates without First Growth pricing

-

earlier consumption windows (driving market demand)

-

long-term stability and predictable growth

In short, second wines are one of the most efficient ways to gain exposure to the upper tier of Bordeaux wines while balancing cost and performance.

Final thoughts

Second wines from Bordeaux – whether Les Forts de Latour, Le Petit Mouton, Pavillon Rouge, Carruades de Lafite, or Le Clarence de Haut-Brion – offer compelling value for both collectors and investors. While they may not always achieve the prestige of their Grand Vins, their strong brand associations, increased affordability, and favourable ageing dynamics make them attractive assets within a diversified wine investment strategy.

As global demand continues to grow, particularly for leading estates in the Médoc and Graves, second growth Bordeaux wines and second labels are likely to remain a highly relevant segment of the fine wine market.

FAQ: Second Wines

What are second wines in Bordeaux?

Second wines are wines made by top Bordeaux châteaux using fruit from younger vines or parcels not selected for the Grand Vin.

Are second wines considered good for wine investment?

Yes. Many second growth Bordeaux wines and second labels have demonstrated strong long-term performance.

How do second wines differ from the Grand Vin?

While they come from the same vineyards and winemaking teams, second wines are generally earlier-drinking and less complex. The key difference is selection – the Grand Vin uses only the highest-quality fruit.

Why are second wines cheaper than First Growths?

Price differences reflect hierarchy, brand prestige, and selection. First Growths such as Lafite Rothschild, Mouton Rothschild, and Haut-Brion command premium pricing due to their status in the 1855 Classification. Their second wines, like Carruades de Lafite or Le Petit Mouton, offer similar pedigree at a fraction of the cost.

Do second wines age well?

Yes, though typically not as long as their Grand Vins. They often reach peak condition earlier, making them attractive for both drinkers and investors.

Which second wines show the best historical performance?

Over the past decade, leading performers include:

-

Le Petit Mouton de Mouton Rothschild

-

Le Clarence de Haut-Brion

-

Carruades de Lafite

-

Pavillon Rouge du Château Margaux

These wines have delivered returns between 63% and 112%, depending on estate and vintage.

Are second wines a good entry point for Bordeaux investment?

Absolutely. They offer affordability, strong brand recognition, and proven liquidity, making them one of the most efficient ways to gain exposure to top-tier Bordeaux wines.

WineCap’s independent market analysis showcases the value of portfolio diversification and the stability offered by investing in wine. Speak to one of our wine investment experts and start building your portfolio. Schedule your free consultation today.